Israel’s long-threatened invasion of Rafah has begun. Under cover of intense aerial bombardment Tuesday morning, Israeli forces moved into Gaza’s southernmost city, which has become a shelter for 1.5 million Palestinians with nowhere else to go. This is the moment they most feared, carrying the potential for a catastrophe greater than anything we’ve seen so far. Gazans counted on the world to stop this invasion, and the world let them down.

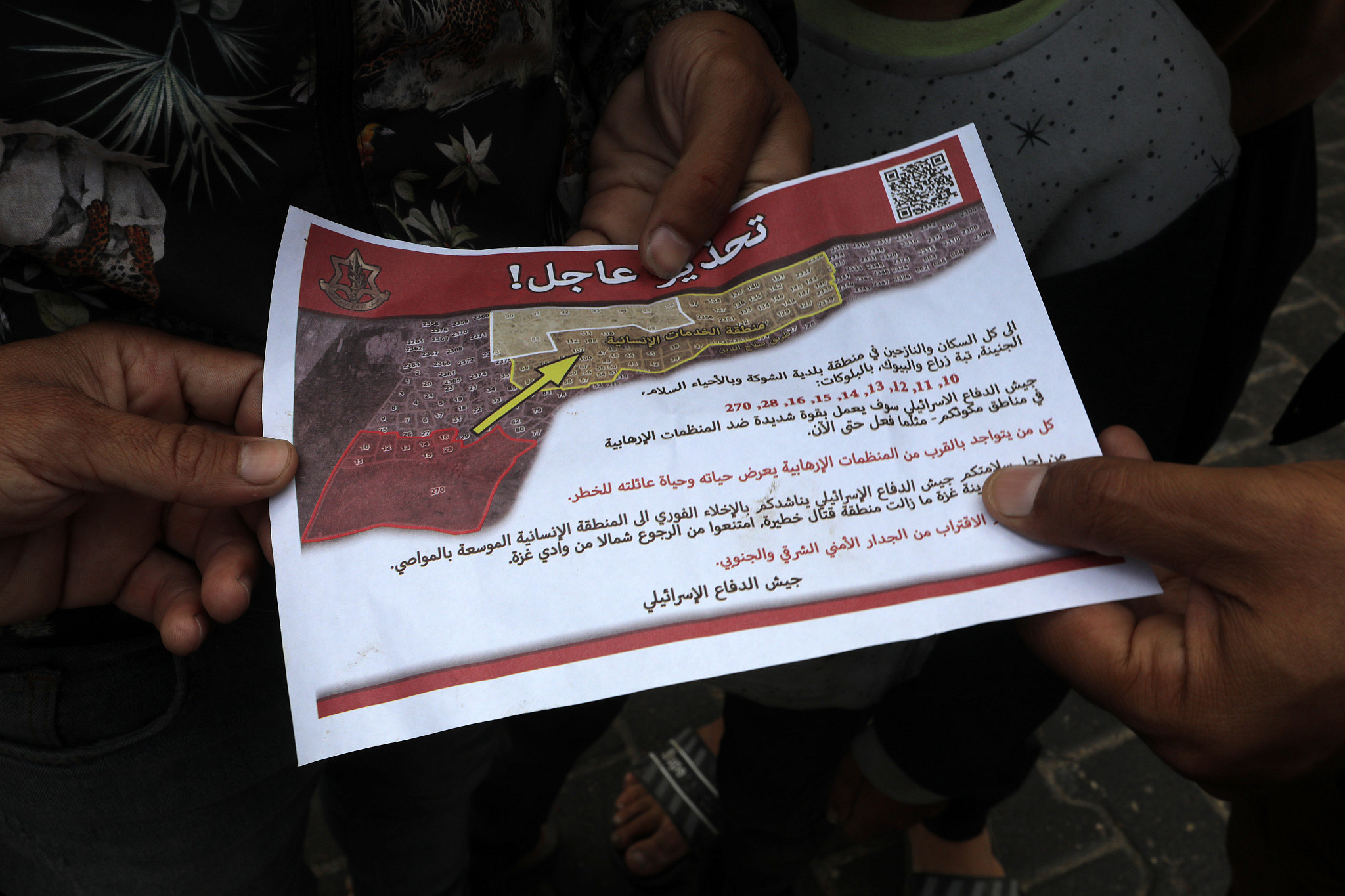

Residents of Rafah have long been in a state of panic in anticipation of this eventuality. That panic intensified Monday morning, when the Israeli army dropped leaflets from the sky ordering those living in Rafah’s eastern districts to immediately flee to the ill-equipped coastal area of Al-Mawasi.

Within hours, tens of thousands packed up what remains of their lives — many of them for the third, fourth, or fifth time since October — and headed northwest to what Israel is calling an “expanded safe zone.” But if Palestinians have learned anything from the past seven months, it is that nowhere in Gaza is ever safe from Israel’s onslaught.

“Since the first day of displacement, I have been living in fear,” 48-year-old Reem Al-Barbari told +972. “I was displaced from Gaza City five months ago and took refuge in Rafah straight away, as the army told us it was a ‘safe area.’ But on Monday morning, leaflets fell instructing us to evacuate, and there was intense bombing throughout the night into Tuesday.

“The sky turned red from the intensity of the explosions,” Al-Barbari continued. “We were unable to sleep at all as we waited for the morning hours to uproot our lives again. The streets were very crowded with citizens — everyone was fleeing.”

Al-Barbari had hoped that when the time finally came to leave Rafah, it would be to return to her home in the Zaytoun neighborhood of Gaza City. “I left crying,” she said. “We went to look for somewhere to stay around Al-Mawasi, where I have no relatives or friends. We were hosted temporarily by other families displaced from Gaza City until we found a tent for ourselves.

“The situation is very painful,” Al-Barbari added. “Our feelings cannot be expressed in words. We are living through a cruel injustice, and the war is only intensifying. We, the citizens, are its victims.”

‘It felt like I was leaving this house forever’

Despite warnings from humanitarian organizations, U.S. President Joe Biden’s claim that a Rafah invasion would be a “red line,” and Hamas’ acceptance of the latest Egyptian-Qatari ceasefire proposal — triggering fleeting celebrations among Palestinians across Gaza — the Israeli army pressed ahead with its incursion amid a blaze of fire near the Egyptian border. Since then, artillery and bombings have continued relentlessly.

For now, the operation is focused on the city’s eastern area and the Rafah Crossing between the Gaza Strip and Egypt — the only route to the outside world for the severely wounded, the extremely sick, and those lucky enough to be able to pay for their escape. The nearby Karem Abu Salem/Kerem Shalom Crossing was also closed for several days, sealing off access to essential humanitarian aid for the residents of the south; on Wednesday morning, Israel reportedly reopened it.

Maryam Al-Sufi, 40, is from Al-Shoka, one of Rafah’s eastern neighborhoods, from which Israel ordered residents to flee. “I was on my way to buy some vegetables from the market, and I heard many people saying that the army dropped leaflets on Al-Shoka and its surrounding areas,” she told +972. “I ran home to confirm the news, and found neighbors out in the street talking about this.

“I was very confused and did not know how to make the decision to leave my home,” Al-Sufi continued. “My husband and his brothers decided it was necessary for the safety of our children; there were scenes of children being bombed in their homes. But I loved all the things in my house. I started collecting the items we would need and a lot of my children’s clothes. It felt like I was leaving this house forever.”

Al-Sufi and her family packed up their belongings and went to stay with relatives who own a cafe on the coast. “The street was crowded with cars and trucks transporting displaced people,” she recalled. “As we fled, we saw bombs falling in the eastern areas of the city.

“We are forced to cry,” she continued. “No one can protect us from the bombing. We used to say that Rafah is safe — we took in our friends and relatives [who fled from other parts of Gaza]. But the army attacked all areas and did not spare anyone.

“We are displaced out of fear for our children,” Al-Sufi added. “We saw what happened in Gaza City and Khan Younis. We hope that Rafah will not be destroyed and that we will not lose anyone.”

‘We are ensnared in an unending nightmare’

Approximately 100,000 Palestinians were living in the area that Israel ordered to evacuate on Monday. But many more have fled the city since then, fearing that Israel’s invasion will quickly expand beyond its current boundaries and endanger the lives of the entire population.

“We live in a state of acute anxiety,” Ahmed Masoud, a human rights activist at Gaza’s Social Development Forum, explained, warning of the catastrophe that a large-scale incursion would entail. “Most of the displaced people in tents are children, women, and the elderly,” he said, adding that the population has already been weakened by months of exhaustion, hunger, disease, and exposure to the winter cold then summer heat.

Reda Auf, a 35-year-old vendor, told +972 that an atmosphere of panic has taken hold throughout the city since Monday. “People here are afraid,” he said. “They are walking with their bags on their shoulders and their children beside them. Women are crying from the oppression of displacement. They have no confidence in [the mercy of] the army because it does not spare anyone. Dozens of massacres have occurred over the past two days through continuous bombing — not only in the areas that were evacuated to the east of the city, but also in the center and west.

“People are moving their belongings and looking for somewhere to take refuge, but there is no safe place,” Auf continued. “All openings to the outside world have been closed in our faces and no one feels our plight. I will also be looking for a tent for myself around Al-Mawasi, because the army will extend [its invasion] to the west of the city if it does not find anyone to stop this bloody operation.”

“The prospect of evacuation from Rafah fills me with dread,” Abd al-Rahman Abu Marq, who has endured displacement three times since October, shared. “My heart quivers at the sight of leaflets being dropped. I don’t know where we would go or how we would get there. I have a mother who cannot walk long distances, and I am responsible for my sisters.

“I’m trying to formulate contingency plans in case evacuation becomes necessary, but the thought of it fills me with terror,” he went on. “For me, sudden death seems preferable to the agonizing anticipation of what lies ahead.”

“We find ourselves ensnared in an unending nightmare as they breach our borders, seemingly sanctioned by the green light from America,” Abu Salem, a 55-year-old living in a tent in the Tal el-Sultan neighborhood, told +972. “Across all regions of Gaza, the cycle of ground invasions persists, accompanied by atrocities against civilians. Yet the world remains eerily silent, as if oblivious to our plight.”

‘Tents have become a luxury’

The shutting of the border crossings, as well as the forced closure of Rafah’s main medical facility, Al-Najjar Hospital, promises to exacerbate an already dire humanitarian situation for those who remain in the city. Hundreds of thousands are living in makeshift tents that are often unable to fulfill the most basic functions of a shelter, and are ill-equipped to house people for months on end. The quest for basic food supplies long ago became a daily struggle, and the spread of disease is increasingly rampant.

Severe overcrowding and a scarcity of goods have made it virtually impossible for the limited number of vendors and distributors to meet the tremendous needs of the population. Residents are forced to queue in front of stores, often reserving their places before sunrise to ensure they can access the available goods before they run out.

Among those struggling is Hisham Yousef Abu Ghaniama, a displaced father of six, who is staying in the southern district of Tel al-Sultan. With no other means of transportation available, Abu Ghaniama is forced to walk to Rafah’s city center every day — a journey of an hour and a half each way. “We are living in an endless tragedy,” he said. “I am 34 years old, and my hair has become gray from the worries and pains that we face.”

The Abu Ghaniama family, originally from Shuja’iya, east of Gaza City, has endured a harrowing journey since the beginning of the war. Forced to flee their home, they initially sought shelter in UN Relief and Works Agency (UNRWA) schools in the north before being displaced once again to Khan Younis. Their plight took another devastating turn when they were suddenly attacked by the Israeli army in Khan Younis and forced to flee, leaving behind their clothes and personal belongings.

“I don’t understand what is happening to us. The situation has exceeded the limits of logic and reason,” Abu Ghaniama said. “Before the war, I used to ask my children what they liked to eat, but now we are searching for any available food to stay alive. You want to bury yourself when your daughter cries and asks you for candy. How can I make her understand the situation we are living in? For seven months we have been killed and our bodies have shrunk to half their size. After how long will this lead to our death?”

Describing the unforgiving conditions, he speaks of mornings engulfed in suffocating heat and evenings shrouded in bone-chilling cold. “Living in a tent in Tel al-Sultan means suffocating,” he said, with “no clean air available” due to the acrid scent of smoke and the stench of garbage. “Even the most simple things are complicated: taking a nap, sitting quietly with your mother, taking a shower, feeling safe, and not suffering from back pain or exhaustion due to sleeping on the floor.”

According to Ahmed Mamoun, who was displaced from Al-Bureij refugee camp in central Gaza when it came under Israeli bombardment, perhaps the most disturbing thing is the increasing normalization of suffering, as desperation drives people to vie for what now count as personal triumphs. “Tents have become a luxury,” Mamoun said. “If there’s a meter between you and your neighbor, people envy you and say you have a ventilation shaft.”

Yet the prospect of securing a more durable shelter is vanishingly small due to the compounding challenges of the war. Mamoun was forced to make a small tent for his family of seven out of wood and plastic — which cost around $570 to buy. “The price of the equipment I purchased is many times its original price before the Israeli war, due to the scarcity of raw materials at the moment,” he explained.

‘The camp is a breeding ground for sickness’

Food and adequate shelter are not the only necessities in short supply in Rafah; so too are medical facilities, and all the more so in the wake of Israel’s intensified assault. Over the past three weeks, Mahmoud Gohar Al-Balaawi, 62, has traversed the distance from Tel al-Sultan camp to the nearest clinic — a three-hour journey he must make by foot — in order to secure vital medications for managing his high blood pressure and diabetes.

“I am an elderly man; I find myself drained of energy, unsure whether to prioritize my own health, concern for my sons who are besieged in the north, or navigating our displacement in Rafah,” he lamented. “Here, everyone seems preoccupied with their own survival. It’s an endless cycle of anguish. I’m depleted in mind and body.”

Disease is also on the rise — a product of severe overcrowding and the lack of hygiene, running water, and adequate healthcare. Two of the most prevalent diseases are cholera and hepatitis, both of which are spread through contaminated water.

“For us, life here lacks even the most basic necessities,” Fatima Ashour, a mother of three, told +972. “There are no clean bathrooms and no sanitation. Garbage piles up on the ground, and children play in it, unaware of the danger. Every day, I comb through my daughter’s hair, battling the relentless onslaught of lice. You can’t take a single step without brushing up on someone else. We’re packed in like sardines, with no respite in sight.”

Two weeks ago, Ashour’s 6-year-old son Zaid began looking emaciated, and his eyes became yellow with jaundice — an indication of his ailing liver and a telltale sign of hepatitis. He is now largely immobile, and he lay listless in his mother’s arms, his eyes dulled by the weight of illness.

Booking an appointment at one of the city’s few overcrowded hospitals is extremely difficult, and even once an appointment is secured, there may not be the necessary medication or even any doctors available. In the meantime, with no space for isolation, caring for Zaid risks the health of his entire family. “The camp is a breeding ground for sickness,” Ashour said, her voice heavy. “With no access to clean water or proper sanitation, we’re all at risk.”

‘The same killers and the same slain’

The living conditions are such that some of the displaced wonder if they should have fled their homes at all. “I would have preferred to face the peril of Israeli tanks in the north than endure the relentless torment of this mental anguish,” 26-year-old Ahmed Hany Dremly told +972.

Indeed, the sight of massive new refugee camps all over southern Gaza evokes poignant memories for Palestinians, harking back to the experiences of their ancestors during the Nakba.

“We are living in a new catastrophe, a new displacement, where the details almost mirror those of 76 years ago,” said 72-year-old Umm Ali Handouqa, whose family was expelled from Majdal (what is now the Israeli city of Ashkelon) to the Gaza Strip in 1948.

Handouqa recalled her childhood memories of Al-Shati refugee camp, reminiscing about the hardships and tough conditions they endured. The tents gradually transformed into small concrete houses as the temporary became a more permanent reality — and Handouqa fears a similar fate could befall Gaza’s new camps.

Most read on +972

“The echoes of the stories my mother told me about the Nakba resonate in my ears,” Handouqa reflected. “The same scenes and details are repeating themselves, the same oppressor and the same victims, the same killers and the same slain.

“We fled from the north out of fear of Israeli forces entering our homes, killing our children before our eyes, and the fear of women being raped,” she said. “It’s the same reason my father fled from Majdal to Gaza.”